China Can Only Go Forward

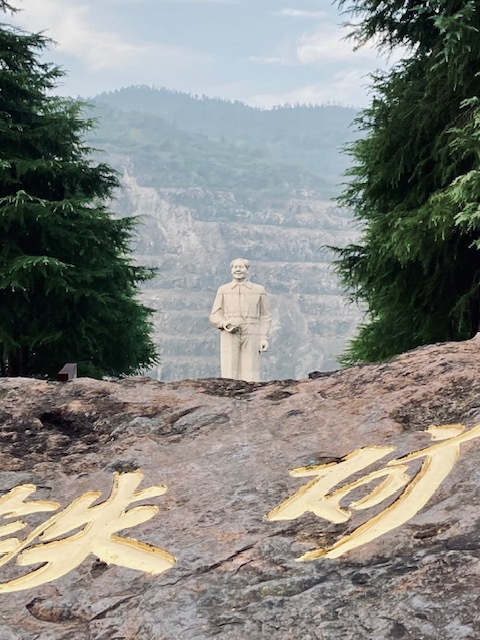

According to a Chinese anecdote, the great reformer leader Deng Xiaoping walked up a mountain in Hubei province to inspect a bridge being built, and when his colleagues wanted to escort him back down the same path after inspecting it, the leader refused, saying, „China can only go forward, not backward”. So the escort and the leader descended the mountain by a new route.This is one of many anecdotes that have been told. It illustrates Deng Xiaoping’s pragmatic and decisive vision of China’s development. His leadership brought about a shift from strict Maoist policies to a model in which China accepted and embraced modernization and seized the opportunity for economic growth. For Deng Xiaoping, the symbol of progress was a symbol of China’s need to continue to develop, both economically and socially, but also to protect itself from extremes. In search of the source and secret of China’s unprecedented development, and following in the reformer’s footsteps, the Magyar Demokrata traveled through China’s Kuangtung and Hupey provinces from Shenzhen to Wuhan in late October.

Awakening

In 2024, subtropical Shenzhen – China’s Silicon Valley – is the country’s third most populous city after Shanghai and Beijing, with a population of 17.5 million. It is home to towering skyscrapers, promenades and boulevards lined with palm trees and maddeningly fragrant purple ivy, internationally renowned architectural marvels and skyscrapers, and even the twin of the Hungarian Palace of Arts, the Müpa Budapest.

Gábor Zoboki, the designer of the Palace of Arts, designed the Nansan Cultural and Arts Center in Shenzhen, which recently hosted the Chinese premiere of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical Cats. It would be easy to believe that the bustling metropolis has always offered this standard of living. That’s why it’s important to understand the journey that led here. Shenzhen was a small, sleepy rural village, subsisting on low-productivity agriculture and fishing. It had no industrial base or economic infrastructure. In the 1980s, it was a backward and impoverished little village, like so many others in rural China. There were dirt roads everywhere, no tall buildings like today, no modern facilities. The infrastructure was rudimentary, the housing modest and lacking in amenities, often including toilets. Life in Shenzhen was based on small markets and family farms, supplied by local artisans. Close by was Hong Kong, a magnet for talent; the city-state was already a thriving global port and financial center. When Deng Xiaoping came to power in the late 1970s, he implemented a series of economic reforms that radically changed China’s trajectory; it is no coincidence that he is revered as the father of reform and opening. The 1980s was a momentous year for Shenzhen: it was the first special economic zone in China, which meant it could experiment with market-oriented economic policies and attract foreign investment. This opportunity spurred rapid industrialization, massive urban development and population growth, as people from all parts of China flocked to the region in search of work and economic opportunity. In just a few decades, Shenzhen went from a small fishing town of 300,000 people living on a shoestring (a different scale in China) to one of the fastest growing cities in the world, but more importantly, it became the first success story of Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening-up policy.

Although international tourist interest is focused on the typical attractions such as the Ping-An Financial Center and the KK100 building, as well as the Shenzhen Civic Center, to understand China, a visit should start at the Museum of Reform and Opening Up, because this is the only way to really understand the discrepancy that still exists in some places between the level of development of the still developing regions and the level of development of the big cities that are already in the 22nd century.

We need children

But development cannot be effective without children. China’s government officially acknowledges the country’s low fertility rate, which, according to the latest figures, is around 1.1 to 1.2. This is well below the 2.1 needed for population stability. However, various government initiatives to encourage childbearing and larger families are showing results. Nothing happens by accident. Between 1980 and 2015, China’s one-child policy, which faced food challenges in the 1980s, curbed population growth that seemed daunting at the time, but also changed the vision of society that now needs to be corrected. The Shenzhen Women and Children’s Center is dedicated to promoting motherhood and childbearing, serving as a daycare, nursery and play center during the day, a community space in the evening, and a social hub late at night that looks like the main square of a beach resort after dark. China’s still-low fertility rate is due to a combination of social, economic, and political factors. The cost of living, including housing, education and health care, is higher in large cities, which still discourages many young people and families from having one or more children out of prudence. The Chinese government has responded vigorously, and today housing and food are affordable, fulfilling some of the hopes raised. Not surprisingly, „Westernization” is also making the situation more difficult. As more Chinese women enter the labor market, many are delaying marriage and childbearing to focus on building their careers. This shift affects fertility, as delaying marriage and childbearing logically leads to fewer children. As a result, the role of grandparents is taking on new importance in China, with the emergence of super-grandparents. During the day, wherever you go in China, babies and children of kindergarten age are cared for by their grandparents. This means that in a country with a mostly pleasant climate, it is the elderly behind the strollers who are busy walking, feeding and changing the babies, who in turn – as a side effect – provide the elderly with love bombs. Win-win, one might say, because the sense of caring, of duty, of mission, gives a retired citizen a new sense of purpose. In China, caring for the elderly is part of both traditional values and formal legal structures. The Law on the Rights and Protection of the Elderly, which has been updated several times, is one of the main legal frameworks that defines the rights of the elderly and their responsibilities for care. The law emphasizes the responsibility of children, a deeply rooted Confucian principle that requires adult children to support and regularly visit their elderly parents. And this is not some unenforceable overregulation. Chinese people are like a leaf returning to its roots. But let’s look at the legal side. Adult children are legally obligated to provide for the material and emotional well-being of their aging parents. Failure to provide such support has legal consequences. In China, this is not over-regulation, but the preservation of an ancient order, an order written down only so that generations born under modern conditions in the 22nd century will not forget it.

New Car Revolution

During our fall trip to China, the Magyar Demokrata visited two automotive giants – both high on the Fortune Global 500 list – BYD in Shenzhen and Dongfeng in Wuhan. What we do know about the Chinese auto industry is that a number of Western automakers produce vehicles in China through joint ventures or wholly owned subsidiaries. Some notable examples include Tesla, BMW, Volkswagen, Ford, General Motors, Honda, Mercedes-Benz, etc. These companies benefit from China’s extensive manufacturing capacity and access to a huge consumer base. The growing demand for electric vehicles is also boosting their statistics as China moves towards a green automotive industry. The West, while attacking China by all means, is very fond of Chinese money, as the Starbucks cafes popping up in our faces at every turn in Chinese cities are a perfect illustration, but what about the competition in the automotive sector? Where does China and the Chinese auto industry stand today? On the face of it, there is a wide variety of cars on the road. Walking around Shenzhen or Wuhan, there are now as many foreign brands as Chinese, but one thing that sets the Chinese competing brands apart is that they are a visual delight with their liberated, bold and unconventional shapes. BYD, Geely, Dongfeng, Great Wall, SAIC, Wuling, Nio, Xpeng and many other carmakers are churning out ever more spectacular vehicles that make their European rivals, especially the jewels of the German car industry, look like gray mice. No wonder the EU is trembling. Chinese automakers have a number of competitive advantages over global automakers. These advantages allow them to become fearless market players and champions of the future. The Chinese government is investing heavily in R&D and production of electric vehicles, giving innovation a space unimaginable anywhere else. There is also a clear direction of travel: towards „Transport 2.0”, the accumulation of unconventional achievements that differ from and go beyond traditional achievements in Chinese vehicles.

The Magyar Demokrata last reported from the city of Chengdu in August (9/16/2024, China must be reckoned with – Our exclusive report from Chengdu), where we tested a 48-lane intersection in the metropolis of 21 million to understand what traffic 2.0 is all about. A quote from the report: Out of curiosity, I go out to this mother of all intersections and watch for minutes as the flood of cars moves with effortless ease across forty-eight lanes. I’ve seen this in America from above and up close, but the noise and smell, like the Astoria in Budapest, bordered on the unbearable. So here I am, and all I can hear is the low purr of electric cars and the occasional perfected hybrid or gasoline car. Thousands of scooters also swarm here, but they are also electric. Perhaps only bicycles are quieter. And then, like an old acquaintance, Europe announces itself with the crackling sound of a diesel engine, and the idyllic scene is interrupted, but only briefly, by a huge garbage truck.„ As for Chinese carmakers, BYD, NIO and Xpeng are leaders in the electric car industry, producing a wide range of models that – crucially – are more affordable than their foreign counterparts. Translated into Hungarian, these cars cost half to a third of the price of brands on the European market. Among their unbeatable innovations are advances in battery technology, including batteries that are economical and actually allow long range. Who wouldn’t consider an electric vehicle if it promised a thousand kilometers of range of a better European diesel car and an even more competitive price? And that’s the basics today. BYD also offers a product in Hungary with a range of over a thousand kilometers, but in Shenzhen there is also a BYD hybrid model with an average fuel consumption of 2 liters and a range of 2,100 kilometers. Got your attention?

Another big draw for Chinese manufacturers is that they have invested heavily in smart car technology, including autonomous driving systems, advanced entertainment IT and connectivity features, which they are incorporating into their cars at affordable prices. Where is this going? During our trip to Wuhan, China, we rode in self-driving electric taxis on public roads. In China, the future has already begun. The Asian giant is now the world’s largest automotive market, giving local automakers – incredibly sophisticated by Western standards – a huge domestic base to test vehicles before expanding globally. And that large consumer base generates significant revenues that can be reinvested in research and development, and the winner of the game is the one with the bigger development budget. The Chinese auto giants are churning out patents by the thousands and tens of thousands and absorbing the best engineers in the world. Talk about engineering education. It is worth taking a moment here. China leads the world in engineering education, with 40 percent of its students in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics). Russia ranks second (35), followed by India and Germany (30), and the US at the bottom with 20 percent. Chinese automakers are now increasingly focused on exporting vehicles to other markets. These include Europe, Asia, and South America.

There is life in the countryside

The news is always about metropolises, and the Magyar Demokrata has also mainly reported on metropolitan environments, with the exception of our report on the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, which, due to the characteristics of the area, presented a dimension beyond the metropolis. In China, the countryside has a serious role to play and a vision for the future, albeit in a different way than we think. But let us start at the beginning. The importance of Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening-up policy has already been mentioned, but what was and is the state of the countryside, which received less attention in the first great wave of development? At that time, rural life was characterized by poverty, illiteracy, and lack of access to modern agricultural techniques. Revitalizing the countryside became an urgent task for China. One of the first steps was the so-called ”toilet revolution,„ in which toilets and sewage disposal and treatment infrastructure were built for the population. This perfectly illustrates the point: to create a humane and livable environment that respects the diversity of nature, to ensure the sustainability and dignity of rural life, and to create viable and useful communities in the face of unstoppable urban development. Thus began a great new era for the countryside, with the eradication of extreme poverty and the revitalization of the countryside. In China today, there is a social consensus that the masses, though living in the metropolises, are fed by the modernizing and automating countryside. Members of rural communities have not sat back, and self-organization has begun everywhere under the coordination of local Party leaders. The rural communities that have developed are divided into districts, each with its own coordinator (leader) who monitors the needs and demands of the people in the district and takes immediate action on any matter, be it health or administrative.

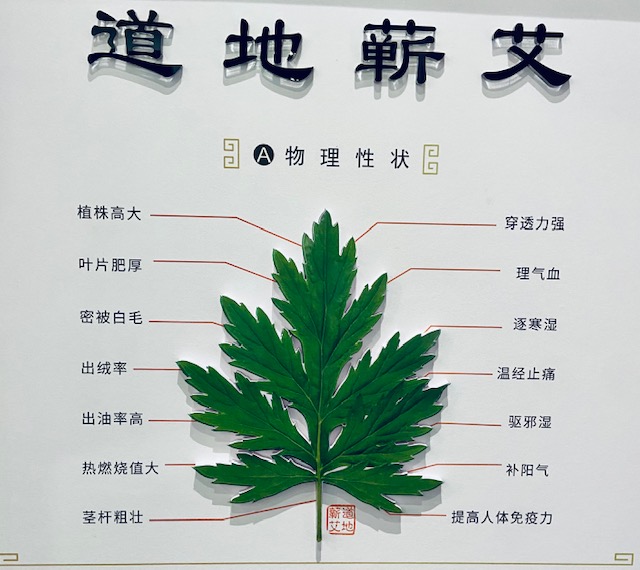

Every villager has a job to do, some voluntary and some paid, as the community also earns money. What they produce on their own and the community’s land is sold or processed by local or foreign contractors who return. And the system takes great care to ensure that villagers receive a fair wage for their work. Another peculiarity of the Chinese countryside is the large number of elderly and very young people whose parents work in the big cities and live in peaceful and safe conditions. Their lives are helped by local volunteers who constantly assess and meet the needs of each family. This is why the ”Love Bank„ was created, where young people volunteer to help the elderly, this is registered by the local authorities (this is the ”deposit„) and when today’s young volunteers become elderly themselves, they will also receive the care and attention. There is also a pension for years of service, now mainly paid by companies, but the state has made it a priority to take over this role. Of course, there is no harm in staying healthy in body and mind. The elderly and the young all live consciously, and those who can also keep a complete ”pharmacy„ of herbs in their own gardens. China’s national pride is its medical and technological industry, which has a thousand-year history of Chinese medicine. Its basic principle is that the human body and soul should be in harmony with nature and the energies that flow within and around us. In Chinese medicine, illness is a sign of imbalance, and the focus of state-supported medicine, which relies on the power of nature rather than symptomatic treatment, is on preventing illness rather than treating symptoms as in the Western world.

Youth, renewal

The standard of living is high, the community and the state are attentive and supportive, and progress is relentless and spectacular. No wonder China’s citizens are proud again. Young people seem to feel that it is good to be Chinese, and although they dress in Western fashion – even if they wear Chinese designer brands – they no longer want to be American. But it is also true that there is a lot of competition, and many feel overwhelmed by the intense competition for better university places and jobs, and by the social expectations mentioned earlier. The relentless competition for housing, jobs, and social status has been recognized by the state in good time, and serious measures have been taken to alleviate the pressure on young people. This is also important because it is from them that China expects a better fertility rate than at present. And the state has a role to play in addressing the negative social trend, formerly known as the ”four no’s,„ that is actually passive and spreading among young people, namely, that young people who are trying to escape the pressures on them do not want a job, do not want a partner, do not want children, and do not want a home. Anyone who travels to China today can see what this means in reality: state-subsidized housing, stable and inclusive jobs, and very affordable food and restaurant prices, all in an extremely clean and safe environment that allows for relaxation, retreat, and fun.

Today’s Chinese youth are already confident and focused on personal development and opportunity. Among them, one of the most important feelings is belonging to a community, experiencing unity. There is a growing appreciation for entrepreneurship, with many young people eager to venture into new industries and technologies, especially in areas such as artificial intelligence. The Chinese government’s initiatives to support education, job creation, and young families are also viewed positively, as these efforts are guaranteed to improve their standard of living and future opportunities and circumstances. This supportive environment is now leading young people to believe in a brighter future. The child is the embodiment of this: the belief that there is a future. While many people still express concern about the pressures of modern life and competition, young people are young, resilient to life’s trials and tribulations, and quick to adapt. It is the balance of hope and reality that shapes their outlook in today’s China, and hope has arrived with the future after nearly fifty years of building at a relentless pace.